Though Piece

As a reminder, the Paris Agreement is a voluntary accord, with many unreliable countries, no accounting standards and no independent verification.

At Bonn recently, the international technocrats have been arguing that they are the only ones to be trusted, because they are intellectually and morally superior to the private sector. Pascoe Sabido, Corporate Europe Observatory, put it this way: “If we are going to ramp up ambition, then we need to ensure the fossil fuel industries are kept out these talks.”

Certainly, the European Union’s obvious prejudices against fossil fuels continue unabated, but the anti-intellectualism is also obvious. They still lack a sense of economic empowerment and practical solutions. To this day, they are ignoring the economic and environmental benefits of measurable, verifiable, and scalable energy efficiency. EE should be eligible for emission trading, just like wood chips.

P.S. “In all likelihood, the United States will live up to its Paris commitment, not because of the White House, but because of the private sector,” noted Erik Solheim, UN Energy Program chief, recently.

UN climate stalemate sees extra week of talks added

Poorer nations say they are fed up with foot dragging by richer countries on finance and carbon cutting commitments.

Some countries, led by China are now seeking to renegotiate key aspects of the Paris agreement.

An extra week of talks in September has been scheduled to try and get the process back on track.

The signing of the Paris climate agreement in 2015 was seen as a momentous achievement, but in retrospect doing the deal might have been the easy part.

In the intervening two and a half years, UN delegates have become increasingly stuck as they work through a welter of technical and accounting rules that will make the Paris pact operational in 2020.

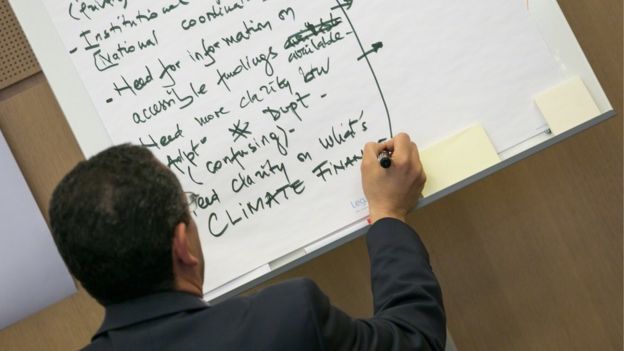

Image copyright IISD/ENB – Kiara Worth

Image copyright IISD/ENB – Kiara Worth Poorer countries have become frustrated by what they see as the cavalier attitude of the rich to the urgency of the problem of rising seas and devastating floods and storms.

“The developed world has to lead,” Amjad Abdulla, the lead negotiator for the Maldives told BBC News.

“We have a huge void – the action (by rich countries) on cutting carbon before 2020 we haven’t really fulfilled that – and we are already embarking on rules for post 2020, that’s unfair.”

Follow the money

Climate finance is almost always the root of some of the biggest arguments in this process. Here in Bonn the developing world have pressed hard to get commitments from the richer nations about a timetable for the monies to be delivered into the future.

For many delegates like Amjad Abdulla, this question of trust on finance is critical, not just in dealing with the impacts of climate change but in helping developing countries shoulder the burden of cutting emissions and moving to renewable energy.

“The developing world’s commitments are unconditional but there are limitations, you have to face the reality, we are living in a limited world. If your hands are tied up there’s no way you can move, you need to unlock and money is the key.”

Image copyright IISD/ENB – Kiara Worth

Image copyright IISD/ENB – Kiara Worth These frustrations have led China to try and renegotiate a fundamental aspect of the Paris deal – the idea that all nations, rich and poor alike, will take on commitments to cut carbon.

“The signals they have been giving here have not been really helpful and have on the contrary been quite negative,” said Ulrikka Aarnio, an observer from campaigners, the Climate Action Network.

“There are a number of countries that need finance for mitigation, adaption and for impacts and China is part of that group and may want to support them. It may be a negotiation tactic at this point.”

Resistance to change?

The Chinese idea that going “back to the future” might be best for developing countries has also shown itself in a dispute over what seems the relatively trivial issue of a name change. The UN proposed last year to alter the clumsy “UN Framework Convention on Climate Change” to the simpler ‘UN Climate Change’.

This proposed new wording has caused upset among some delegates because it drops the word convention from the title.

Signed back in 1992, the Framework Convention divided the world into the rich who were obliged to cut their carbon and the poor who were free to continue using fossil fuels.

“Everything we have undertaken is under the Framework Convention. I don’t think we are going to change that, it has to stay – the bedrock is the convention, the foundation is the convention. We are working, we are building on that. Changing that would be a very bad idea.”

The slow progress here means that an extra session of talks has now been added to the calendar for September to try and make progress before ministers gather in Poland for the crucial Conference of the Parties in Katowice in December.